At a moment when there is all too much talk in Washington about deregulation, a helpful counterpoint has arrived from the Political Economy Research Institute in the form of the latest edition of the Toxic 100, a compilation of the companies responsible for the highest volumes of industrial pollution.

At a moment when there is all too much talk in Washington about deregulation, a helpful counterpoint has arrived from the Political Economy Research Institute in the form of the latest edition of the Toxic 100, a compilation of the companies responsible for the highest volumes of industrial pollution.

The project, which has been providing this information since 2004, now has rankings on three kinds of pollution: air, water and greenhouse gases. The lists include environmental justice indicators that highlight the disproportionate effect on low-income and minority communities.

The companies on these lists represent some of the biggest threats to the physical well-being of the people of the United States.

The top tier of the air pollution list, which is based on data from the EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory, contains the kind of industrial giants one might expect: DowDuPont, General Electric, Royal Dutch Shell and Arconic (a spinoff of Alcoa). Yet number one is the less well known Zachry Group, an engineering company that operates dirty manufacturing facilities in North Carolina and Texas. Also in the top ten is Berkshire Hathaway by virtue of its ownership of companies such as Johns Manville, Pacificorp and MidAmerican Energy.

The top tier of the greenhouse gas list, based on other EPA data, is dominated by companies operating lots of fossil fuel power plants: Southern Company, Duke Energy, American Electric Power and NRG Energy. These are the companies Trump is aiding with his attack on the Obama Administration’s Clean Power Plan.

Berkshire Hathaway is the only parent company in the top ten on both the air and greenhouse gas lists; it ranks 21st in water pollution.

I could not resist the temptation to check where the companies that rank high on the Toxic 100 lists show up in Violation Tracker. This is partly because Rich Puchalsky, who serves as the data management specialist for the Toxic 100, has also played an essential role in the construction and expansion of Violation Tracker.

Rich kindly created for me a spreadsheet combining rankings from the two projects. Looking first at the Toxic Air 100, I see there are unsurprising overlaps with the 100 most penalized companies in Violation Tracker—BP, Exxon Mobil, Royal Dutch Shell, Phillips 66, etc. Yet there are some very large air polluters that have faced much smaller penalties, including the Zachry Group cited above and TMS International, a steel industry service company. The EPA should take note.

As for the Greenhouse 100, there are expected overlaps with the Violation Tracker top 100—such as Duke Energy, American Electric Power, FirstEnergy, etc. But there are some discrepancies. Large CO2 emitters such as Energy Future Holdings, Great Plains Energy, and OGE Energy have not received substantial penalties. The EPA might want to check these as well.

Beyond the specifics of individual companies, there is a broader issue here: what is the connection between fines and emissions? Although the releases reported in the Toxic 100 are technically not illegal, those companies are likely to be creating unsanctioned emissions as well. Fines could bring about reductions in both categories. Yet many big polluters treat the penalties as a tolerable cost of doing business and fail to do enough to clean up their facilities. That suggests the need for newer and more effective forms of enforcement. Deregulation is not one of them.

It’s unclear to what extent the Obama Administration’s practice of extracting unprecedented monetary penalties on miscreant companies proved to be an effective deterrent, but at least the billion-dollar fines and settlements served to highlight the ongoing problem of corporate crime.

It’s unclear to what extent the Obama Administration’s practice of extracting unprecedented monetary penalties on miscreant companies proved to be an effective deterrent, but at least the billion-dollar fines and settlements served to highlight the ongoing problem of corporate crime.

Donald Trump got a lot of mileage during his presidential campaign from criticizing the poor record of wage growth during the Obama era. Since taking office he has done nothing to directly address the issue. In fact, his administration’s attacks on labor rights have made it more difficult for workers to push for higher pay through unions.

Donald Trump got a lot of mileage during his presidential campaign from criticizing the poor record of wage growth during the Obama era. Since taking office he has done nothing to directly address the issue. In fact, his administration’s attacks on labor rights have made it more difficult for workers to push for higher pay through unions. Money laundering has jumped back to the top of the corporate crime charts, thanks to Steve Bannon’s statements about Trump’s associates as well as the

Money laundering has jumped back to the top of the corporate crime charts, thanks to Steve Bannon’s statements about Trump’s associates as well as the  The year began with a burst of announcements by the Obama Administration of cases it rushed to resolve before leaving office. In the period between election day and the inauguration, the Justice Department and various agencies announced

The year began with a burst of announcements by the Obama Administration of cases it rushed to resolve before leaving office. In the period between election day and the inauguration, the Justice Department and various agencies announced  When Donald Trump fired dozens of U.S. Attorneys last March, there was speculation that the main objective was to remove some, especially Preet Bharara in Manhattan, who might be investigating the president’s business interests.

When Donald Trump fired dozens of U.S. Attorneys last March, there was speculation that the main objective was to remove some, especially Preet Bharara in Manhattan, who might be investigating the president’s business interests. The world according to Trump is one of grievances and victimhood. During the presidential campaign he got a lot of mileage by appearing to empathize with the travails of the white working class and promising to be their champion in fighting against the impact of globalization and economic restructuring. At times he even seemed to be adopting traditional left-wing positions by criticizing big banks and big pharma.

The world according to Trump is one of grievances and victimhood. During the presidential campaign he got a lot of mileage by appearing to empathize with the travails of the white working class and promising to be their champion in fighting against the impact of globalization and economic restructuring. At times he even seemed to be adopting traditional left-wing positions by criticizing big banks and big pharma. It appears that the Trump Administration will not rest until every last federal regulatory agency is under the control of a corporate surrogate. The reverse revolving door is swinging wildly as business foxes swarm into the rulemaking henhouses.

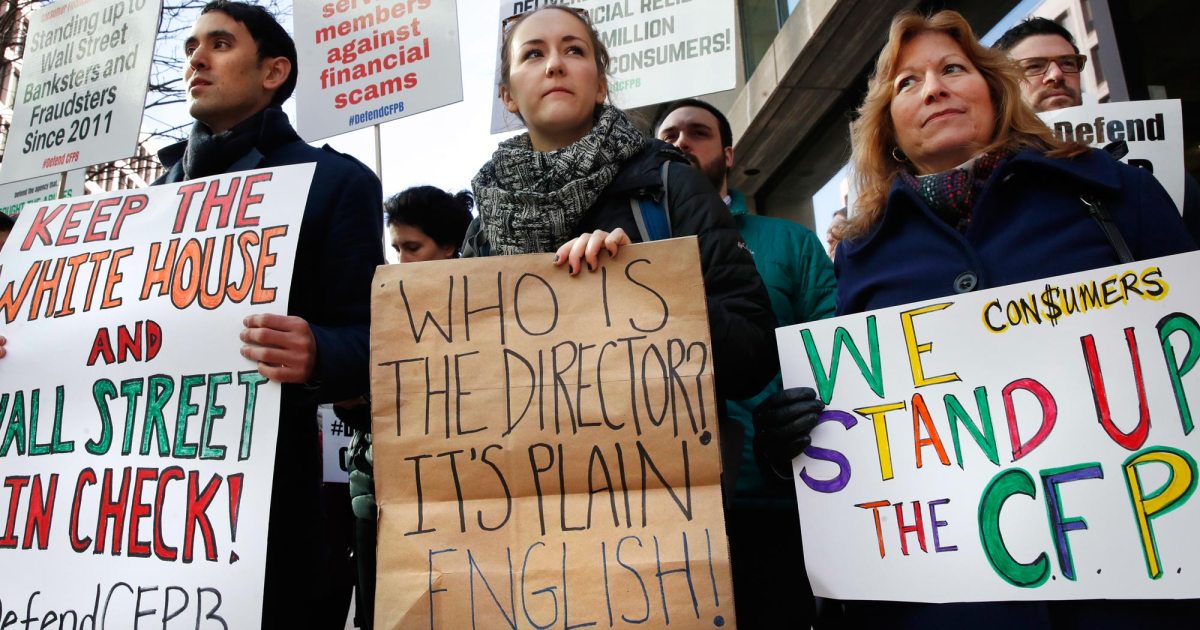

It appears that the Trump Administration will not rest until every last federal regulatory agency is under the control of a corporate surrogate. The reverse revolving door is swinging wildly as business foxes swarm into the rulemaking henhouses.

You must be logged in to post a comment.