.jpg)

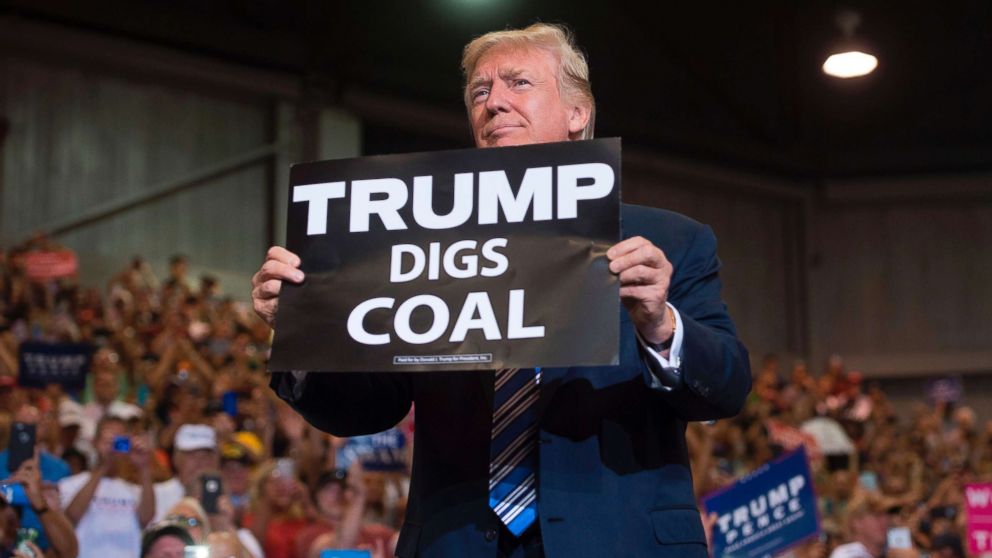

Despite all the effort it has put into eliminating business regulations, the Trump Administration insists that it diligently enforces those rules that are still in effect. Moreover, Trump likes to depict himself as some sort of crusader against corporate misconduct.

A new indication of the absurdity of these claims comes from the U.S. Labor Department, which recently decided it would no longer issue press releases when citing companies for violations of rules governing workplace safety, employment discrimination and labor standards. According to an internal memo obtained by the New York Times, the excuse for the change was that such releases tend to linger prominently in search results and would be misleading if an enforcement action was ultimately found to have been unjustified.

Rarely does an alleged violation turn out to have no basis, and in those very few instances the problem could be resolved by the issuance of a new press release that would presumably circulate as easily as the original one. The real motivation for the change is to reduce the ability of agencies to pressure corporate transgressors and could be a stepping-stone toward the elimination of all announcements of violations.

Some parts of the Trump Administration already seem to have moved in that direction. In the course of collecting data for Violation Tracker, I check the websites of more than 50 federal regulatory agencies every three months to find new cases to add to the database. By the way, only finalized cases are included.

Agencies report on different schedules. Some issue a press release on each case when it is resolved or add each penalty to an ongoing database. Others disclose the data periodically, whether monthly, quarterly or annually.

What I have found is that some agencies seemed to have given up on new reporting even while leaving their historical data in place. Here are some examples:

The Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement, which regulates offshore oil drilling, has no data on its civil penalties page more recent than fiscal year 2018.

The Federal Maritime Commission’s Bureau of Enforcement has not updated its penalty announcements since May 2019.

The most recent item on the Consumer Product Safety Commission’s list of press releases relating to an enforcement penalty is dated November 26, 2018.

It is difficult to determine whether these agencies are not announcing enforcement actions or have stopped bringing them. Either would be troubling.

Publicizing violations and penalties is just as important as the enforcement actions themselves. For many companies, the fines they are required to pay are trivial. The disclosure of their conduct means much more in terms of the impact on the firm’s reputation among customers and investors. Those revelations, called “regulation by shaming” in the academic literature, can have a bigger deterrent effect.

Violation Tracker is meant to enhance the deterrence by collecting a wide variety of disclosures about corporate misconduct and showing the degree of recidivism, especially among large companies. Keeping the database current is a lot easier when agencies are not hiding their data.