For those convinced of the depravity of large corporations and the super-wealthy, recent days have provided an abundance of vindication. Thanks to the whistleblower at Facebook and an anonymous leaker of a vast collection of confidential financial documents dubbed the Pandora Papers, we have amazing new evidence of corruption and anti-social behavior.

Frances Haugen’s release of internal research paints a picture of Facebook as prioritizing profits ahead of taking steps to address evidence that its algorithms promote social animosity and that its products such as Instagram exacerbate mental health problems among teenage users.

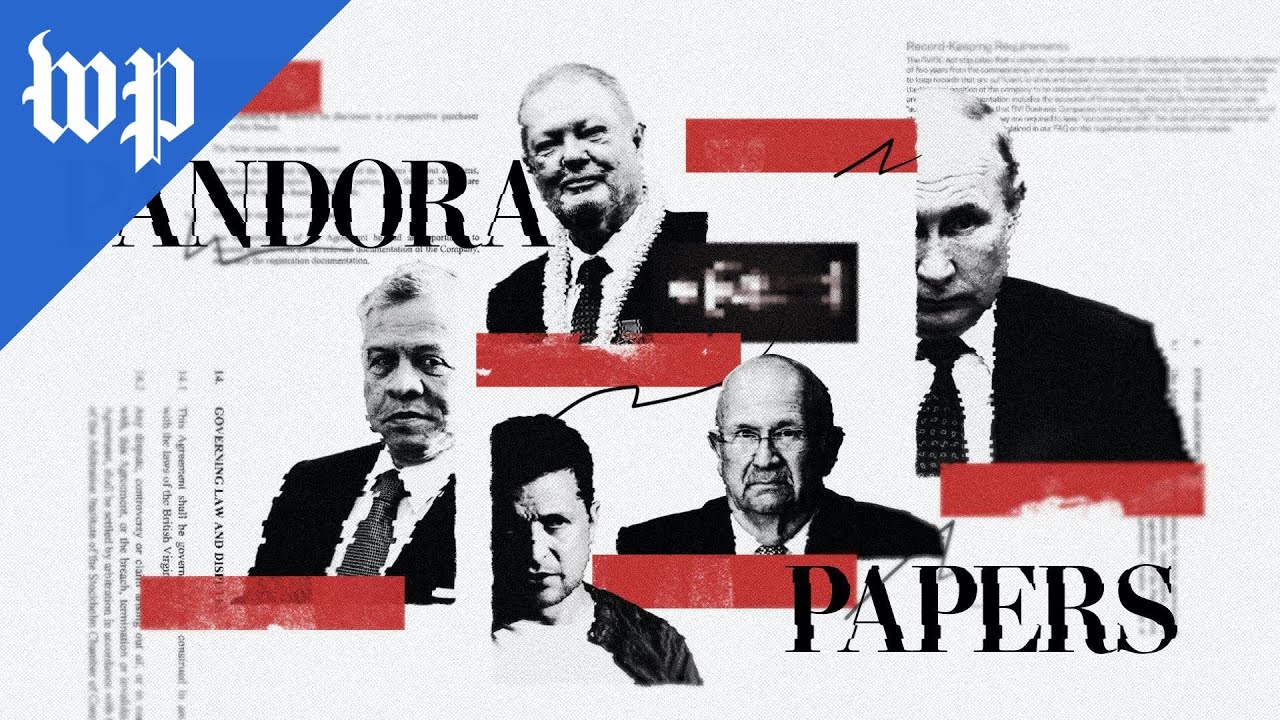

The financial documents revealed in the Pandora Papers depict numerous billionaires and government leaders around the world as brazen tax cheats who are accumulating immense amounts of illegal assets in the form of high-end real estate, yachts and secret bank accounts.

Of course, none of this comes as a surprise. In fact, this is not the first large-scale leak of private financial records showing misappropriation, money laundering and tax evasion among the global elite. We already knew that Facebook is basically unconcerned about the damage caused by its services.

As is always the case after major revelations like these, the main question is whether policymakers will do anything to address the problems. The odds that the Pandora Papers will prompt Congress to act are reduced somewhat by the fact that the disclosures do not include much about members of the U.S. elite. Major controversies have erupted in countries such as Jordan, Kenya and the Czech Republic, whose leaders are among those implicated in the documents. U.S. individuals consist mainly of lesser-known billionaires and art dealers.

Perhaps the most salient U.S. angle in the Pandora Papers is the increasingly important role played by states such as South Dakota as tax havens for elites seeking to shield illicit assets. To some extent this is an issue for state legislatures, though a bill has been introduced in Congress that would require trust companies and others to screen foreign clients seeking to move assets through the U.S. financial system.

There may be more policy momentum when it comes to Facebook. It and the other tech giants have been receiving criticism, for varying reasons, from members of Congress across the political spectrum. Along with the issues raised by the whistleblower, there are increasing concerns about the concentration of ownership within the tech sector. Among other things, Facebook is the subject of a new antitrust complaint by the Federal Trade Commission.

An article in the Washington Post quotes lawmakers suggesting that this may be tech’s “Big Tobacco moment,” a reference to the time in the late 1990s when the major cigarette manufacturers lost their stranglehold over public policy and ended up having to accept stronger federal regulation and paying out tens of billions of dollars in class action settlements.

It is good to hear that legislators are thinking in those terms, but they will have to turn up the heat much higher on Facebook, which so far is not admitting any culpability and whose CEO is too young to remember much about the 1990s.

Kudos to Sen. Elizabeth Warren for introducing a piece of legislation that filters out all the political noise and goes to the heart of one of the most pressing issues of the day: what can be done to change the behavior of large irresponsible corporations? Her answer: quite a lot.

Kudos to Sen. Elizabeth Warren for introducing a piece of legislation that filters out all the political noise and goes to the heart of one of the most pressing issues of the day: what can be done to change the behavior of large irresponsible corporations? Her answer: quite a lot. It is now a full century since the Progressive Era ended some of the worst abuses of concentrated economic power. This year is the 100th anniversary of the Clayton Act and the Federal Trade Commission Act. It is 103 years since the dissolution of the Standard Oil trust, 108 years since the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act.

It is now a full century since the Progressive Era ended some of the worst abuses of concentrated economic power. This year is the 100th anniversary of the Clayton Act and the Federal Trade Commission Act. It is 103 years since the dissolution of the Standard Oil trust, 108 years since the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act. The Big Three carmakers, once considered the epitome of corporate irresponsibility, have been viewed in a more favorable light in recent years.

The Big Three carmakers, once considered the epitome of corporate irresponsibility, have been viewed in a more favorable light in recent years. As the northeast begins to recover from the ravages of Sandy, there are

As the northeast begins to recover from the ravages of Sandy, there are  We Built It. The Romney campaign and the wider conservative movement believe they have a winner in a slogan designed to refute President Obama’s comment about the role of government assistance to business in favor of an idealized Ayn Rand-style entrepreneurship that needs no stinkin’ public infrastructure.

We Built It. The Romney campaign and the wider conservative movement believe they have a winner in a slogan designed to refute President Obama’s comment about the role of government assistance to business in favor of an idealized Ayn Rand-style entrepreneurship that needs no stinkin’ public infrastructure. Wal-Mart’s

Wal-Mart’s

You must be logged in to post a comment.