The world according to Trump is one of grievances and victimhood. During the presidential campaign he got a lot of mileage by appearing to empathize with the travails of the white working class and promising to be their champion in fighting against the impact of globalization and economic restructuring. At times he even seemed to be adopting traditional left-wing positions by criticizing big banks and big pharma.

The world according to Trump is one of grievances and victimhood. During the presidential campaign he got a lot of mileage by appearing to empathize with the travails of the white working class and promising to be their champion in fighting against the impact of globalization and economic restructuring. At times he even seemed to be adopting traditional left-wing positions by criticizing big banks and big pharma.

Over the past ten months that stance has been steadily changing, and now the transformation is starkly evident. Trump is still obsessed with victimhood, but the focus on the legitimate economic grievances of white workers has been replaced by a preoccupation with the bogus grievances of large corporations. He would have us believe that today’s most oppressed group is Corporate America.

The desire to come to the rescue of big business is, when all the distracting tweets are put aside, at the core of the mission that Trump shares with Congressional Republicans: dismantling regulation and slashing corporate taxes.

It’s difficult to know whether this is what Trump planned all along and cynically manipulated his supporters or if he was turned by the Washington swamp he unconvincingly vowed to drain. In either event, his administration is engaging in one of the most egregious betrayals in American history.

Trump is not only neglecting the economic interests of his core supporters; he is siding with those who prey on them. This is playing out in many ways — from promoting anti-worker policies at the Labor Department to going easy on the drug companies responsible for the opioid epidemic — but one of the most revealing situations is taking place at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

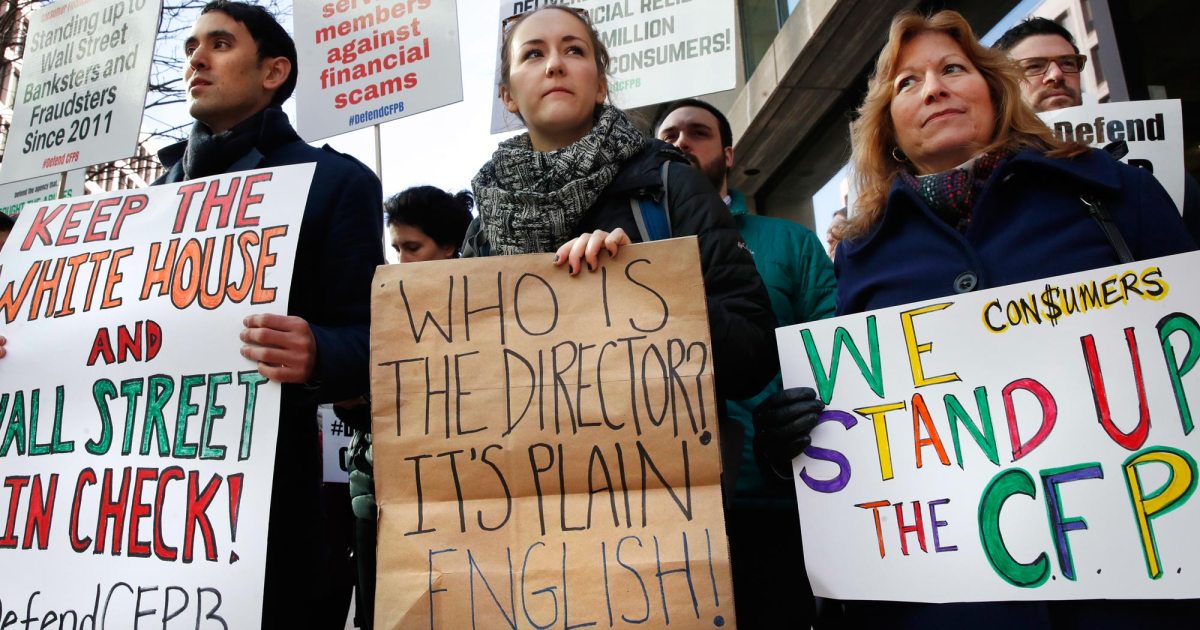

Putting aside the question of whether outgoing director Richard Cordray or President Trump has the right to name an acting director, the real issue is what is going to become of an agency that has been courageous and unrelenting in its enforcement actions against predatory financial firms.

The CFPB’s sin, from the point of view of the White House and Congressional Republicans, is that it has been doing its job too well. One of the dirty little secrets of Washington is that most regulatory agencies are in the pocket of the corporations they are supposed to police. Oversight is usually friendly or at least not onerous.

The CFPB was designed to, and in practice did, break that mold. It has not been chummy with the banks, payday lenders, mortgage brokers and credit agencies. As shown in Violation Tracker, since 2012 the CFPB has brought more than 100 enforcement actions and imposed more than $7 billion in penalties.

After he was named to take over the agency, Mick Mulvaney, who had long advocated its dismantlement, was quoted as saying that President Trump wanted him to get the CFPB “back to the point where it can protect people without trampling on capitalism.” The very thinly veiled message is that CFPB will cease to be an aggressive advocate for consumers, allowing banks and other financial companies to breathe easier.

Mulvaney was giving what amounted to a moral reprieve for all those companies pursued by the CFPB, including:

- Wells Fargo, which was the target of one of the CFPB’s highest profile enforcement actions: the $100 million penalty imposed on the bank for secretly creating millions of extra accounts not requested by customers, in order to generate illicit fees.

- Mortgage loan servicer Ocwen Financial, which the CFPB ordered to provide $2 billion in principal reduction to underwater borrowers, many of whom had been forced into foreclosure by Ocwen’s abusive practices.

- Bank of America and FIA Card Services, which the CFPB ordered to provide $747 million in relief to card customers harmed by deceptive marketing of add-on products.

- Corinthian Colleges Inc., the operator of dubious for-profit schools that was sued by the CFPB and ended up going out of business amid charges that it lured students into taking out private loans to cover expensive tuition costs by advertising bogus job prospects and career services.

- Colfax Capital (also known as Rome Finance), which the CFPB ordered to pay $92 million in debt relief to some 17,000 members of the U.S. armed forces who had been harmed by the company’s predatory lending practices.

- Or smaller operators such as Reverse Mortgage Solutions, which the CFPB fined for falsely telling customers, mainly seniors, that there was no risk of losing their home.

The Trump Administration has come to the rescue of financial scammers such as these by moving to defang the CFPB and restore the proper order of things in which it is not capitalists but rather consumers and workers who get trampled.

It appears that the Trump Administration will not rest until every last federal regulatory agency is under the control of a corporate surrogate. The reverse revolving door is swinging wildly as business foxes swarm into the rulemaking henhouses.

It appears that the Trump Administration will not rest until every last federal regulatory agency is under the control of a corporate surrogate. The reverse revolving door is swinging wildly as business foxes swarm into the rulemaking henhouses. Large corporations in the United States like to portray themselves as victims of a supposedly onerous tax system and a supposedly oppressive regulatory system. Those depictions are a far cry from reality, but that does not stop business interests from seeking to weaken government power in both areas.

Large corporations in the United States like to portray themselves as victims of a supposedly onerous tax system and a supposedly oppressive regulatory system. Those depictions are a far cry from reality, but that does not stop business interests from seeking to weaken government power in both areas. The bizarro-world worker populism of Donald Trump strikes again. The White House recently

The bizarro-world worker populism of Donald Trump strikes again. The White House recently  Once upon a time, there was a debate on how best to check the power of giant corporations. Starting in the Progressive Era and resuming in the 1970s with the arrival of agencies such as the EPA and OSHA, some emphasized the role of government through regulation. Others focused on the role of the courts, especially through the kind of class action lawsuits pioneered by lawyers such as

Once upon a time, there was a debate on how best to check the power of giant corporations. Starting in the Progressive Era and resuming in the 1970s with the arrival of agencies such as the EPA and OSHA, some emphasized the role of government through regulation. Others focused on the role of the courts, especially through the kind of class action lawsuits pioneered by lawyers such as  The withdrawal of Tom Marino’s nomination as national drug czar is a reminder of the power of whistle-blowing and aggressive investigative reporting, while the fact that he was named in the first place is a reminder of the hollowness of the Trump’s Administration’s commitments to draining the swamp and to seriously addressing the opioid epidemic.

The withdrawal of Tom Marino’s nomination as national drug czar is a reminder of the power of whistle-blowing and aggressive investigative reporting, while the fact that he was named in the first place is a reminder of the hollowness of the Trump’s Administration’s commitments to draining the swamp and to seriously addressing the opioid epidemic. The Trump Administration would have us believe it is all about helping workers. Yet it has a strange way of showing it. Policies that directly assist workers are under attack, and all the emphasis is on initiatives that purportedly aid workers indirectly by boosting their employers.

The Trump Administration would have us believe it is all about helping workers. Yet it has a strange way of showing it. Policies that directly assist workers are under attack, and all the emphasis is on initiatives that purportedly aid workers indirectly by boosting their employers. When a new corporate scandal arises, there is a tendency on the part of many observers to treat it as a complete surprise — as something that could not have been anticipated.

When a new corporate scandal arises, there is a tendency on the part of many observers to treat it as a complete surprise — as something that could not have been anticipated. Donald Trump likes to give the impression that he has made great strides in dismantling regulation. While there is no doubt that his administration and Republican allies in Congress are targeting many important safeguards for consumers and workers, the good news is that those protections in many respects are still alive and well.

Donald Trump likes to give the impression that he has made great strides in dismantling regulation. While there is no doubt that his administration and Republican allies in Congress are targeting many important safeguards for consumers and workers, the good news is that those protections in many respects are still alive and well. When Betsy DeVos was nominated to head the Department of Education, the main concern was what harm a “choice” crusader would bring to K-12 public schools. Recently we’ve seen that she can also cause damage with regard to post-secondary education.

When Betsy DeVos was nominated to head the Department of Education, the main concern was what harm a “choice” crusader would bring to K-12 public schools. Recently we’ve seen that she can also cause damage with regard to post-secondary education.

You must be logged in to post a comment.