Donald Trump built his presidential campaign on the claim that he would be a champion for working people, yet his administration finds one way after another to tip the scales in favor of employers. The latest example involves tips themselves.

Donald Trump built his presidential campaign on the claim that he would be a champion for working people, yet his administration finds one way after another to tip the scales in favor of employers. The latest example involves tips themselves.

In December the Labor Department, bowing to the wishes of the National Restaurant Association, proposed to rescind an Obama Administration rule that prohibited employers from pooling tips. The rule had been adopted to prevent restaurant owners from claiming a share of the gratuities.

While the DOL has claimed that the change would benefit back-of-house workers who don’t directly receive tips, groups such as Restaurant Opportunities Centers (ROC) United say that employers often grab a portion of tips when it is not permitted and that legalizing the practice will only encourage owners to take more.

It turns out that ROC United’s position is shared but some at DOL, but those views are being suppressed. Bloomberg has just reported that political officials at the department rejected an internal analysis concluding that workers could lose billions of dollars from tip pooling. DOL sources told Bloomberg that the officials ordered staffers to change their methodology to reach a different conclusion.

Anyone who takes an honest look at the restaurant industry is bound to conclude that employers will do their utmost to exploit tip pooling. After all, these are companies that already steal from their workers through violations of wage and hour rules concerning off-the-clock work, overtime, misclassification and the like.

Consider the large full-service chains such as Darden Restaurants (Olive Garden, Capital Grille and other brands), Brinker International (Chili’s and Maggiano’s), Bloomin’ Brands (Outback Steakhouse and others) and DineEquity (Applebee’s and IHOP). As shown in Violation Tracker, each one of these has had to pay fines to the DOL’s Wage and Hour Division; six times in the case of DineEquity.

The chains have also been targeted in private collective action lawsuits brought by groups of workers. In 2007 Darden agreed to pay $11 million to settle a group of suits alleging that the company improperly classified certain types of workers as exempt from overtime pay eligibility.

In 2014 Brinker International agreed to pay $56.5 million to settle a long-running lawsuit alleging that the company had routinely violated California rules about meal and rest breaks. In 2016 Bloomin’ Brands agreed to pay $3 million to settle allegations that workers at its Outback outlets were required to show up early to perform unpaid pre-shift prep work. DineEquity has faced similar litigation.

Why would anyone think that companies involved in such transgressions would pass up another opportunity to enrich themselves if DOL gives a green light to tip pooling?

Home Depot is the latest company to join the bonus bandwagon, announcing that it will give hourly employees one-time payments of up to $1,000 as a “reward to our associates for continuing to deliver outstanding customer service.” CEO Craig Menear added: “This incremental investment in our associates was made possible by the new tax reform bill.”

Home Depot is the latest company to join the bonus bandwagon, announcing that it will give hourly employees one-time payments of up to $1,000 as a “reward to our associates for continuing to deliver outstanding customer service.” CEO Craig Menear added: “This incremental investment in our associates was made possible by the new tax reform bill.”

Donald Trump got a lot of mileage during his presidential campaign from criticizing the poor record of wage growth during the Obama era. Since taking office he has done nothing to directly address the issue. In fact, his administration’s attacks on labor rights have made it more difficult for workers to push for higher pay through unions.

Donald Trump got a lot of mileage during his presidential campaign from criticizing the poor record of wage growth during the Obama era. Since taking office he has done nothing to directly address the issue. In fact, his administration’s attacks on labor rights have made it more difficult for workers to push for higher pay through unions. Money laundering has jumped back to the top of the corporate crime charts, thanks to Steve Bannon’s statements about Trump’s associates as well as the

Money laundering has jumped back to the top of the corporate crime charts, thanks to Steve Bannon’s statements about Trump’s associates as well as the  The year began with a burst of announcements by the Obama Administration of cases it rushed to resolve before leaving office. In the period between election day and the inauguration, the Justice Department and various agencies announced

The year began with a burst of announcements by the Obama Administration of cases it rushed to resolve before leaving office. In the period between election day and the inauguration, the Justice Department and various agencies announced  When Donald Trump fired dozens of U.S. Attorneys last March, there was speculation that the main objective was to remove some, especially Preet Bharara in Manhattan, who might be investigating the president’s business interests.

When Donald Trump fired dozens of U.S. Attorneys last March, there was speculation that the main objective was to remove some, especially Preet Bharara in Manhattan, who might be investigating the president’s business interests. It’s refreshing to see the book thrown at a corporate criminal, but it would have been even better if federal prosecutors had aimed higher.

It’s refreshing to see the book thrown at a corporate criminal, but it would have been even better if federal prosecutors had aimed higher. The world according to Trump is one of grievances and victimhood. During the presidential campaign he got a lot of mileage by appearing to empathize with the travails of the white working class and promising to be their champion in fighting against the impact of globalization and economic restructuring. At times he even seemed to be adopting traditional left-wing positions by criticizing big banks and big pharma.

The world according to Trump is one of grievances and victimhood. During the presidential campaign he got a lot of mileage by appearing to empathize with the travails of the white working class and promising to be their champion in fighting against the impact of globalization and economic restructuring. At times he even seemed to be adopting traditional left-wing positions by criticizing big banks and big pharma. It appears that the Trump Administration will not rest until every last federal regulatory agency is under the control of a corporate surrogate. The reverse revolving door is swinging wildly as business foxes swarm into the rulemaking henhouses.

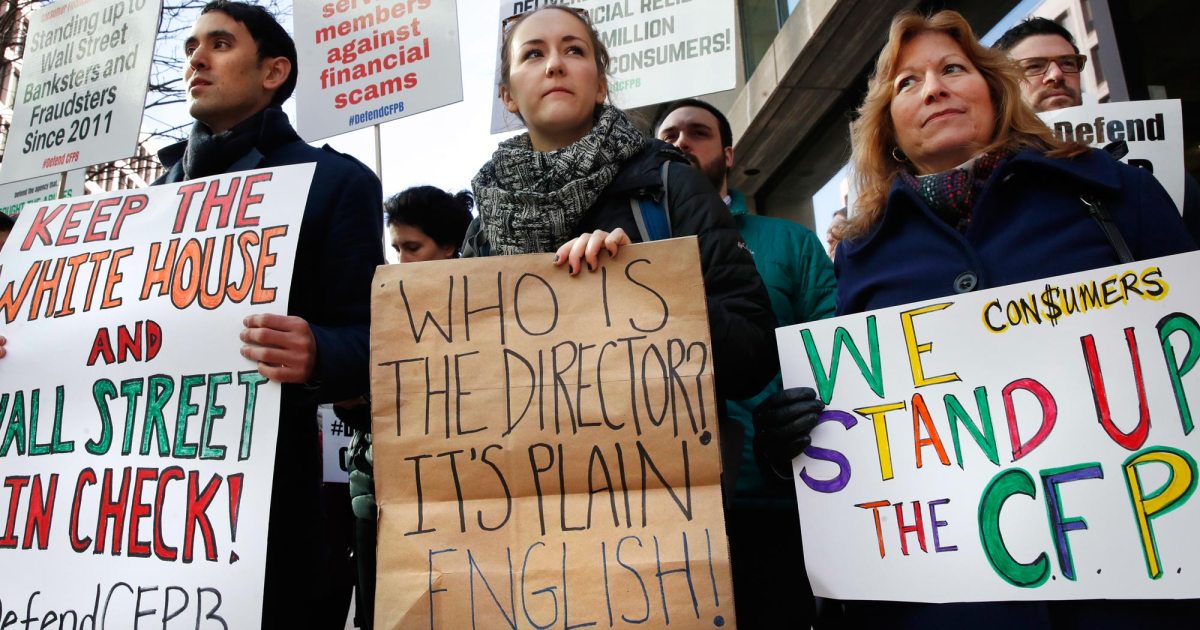

It appears that the Trump Administration will not rest until every last federal regulatory agency is under the control of a corporate surrogate. The reverse revolving door is swinging wildly as business foxes swarm into the rulemaking henhouses.

You must be logged in to post a comment.