When it comes to dealing with egregious corporate polluters, we tend to think first about what the EPA and the Justice Department are doing to address the problem. Yet there is another way in which environmental miscreants can be called to account: private litigation.

For the past half century, a series of major lawsuits have served as the means by which large corporations have been compelled to change many of their worst environmental practices and compensate victims of those abuses.

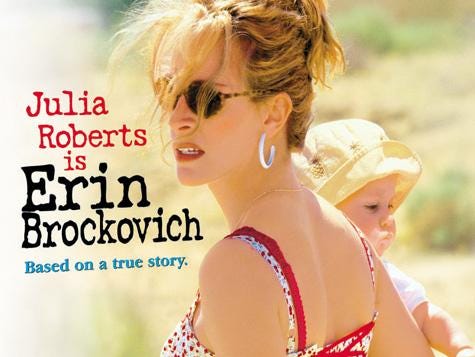

Some of these cases have become legendary and have inspired Hollywood movies. The 2000 film Erin Brockovich told the story of a legal clerk who was central to a successful lawsuit against the utility Pacific Gas & Electric for contaminating the water supply of a California town with the carcinogen hexavalent chromium. The 2019 movie Dark Waters dramatized the efforts of attorney Robert Bilott to get DuPont to take responsibility for exposing residents of a West Virginia community to highly toxic chemicals called PFOAs.

The latest expansion of Violation Tracker includes entries on the PG&E and DuPont cases as well as 100 other lawsuits resolved over the past two decades. As a result of these actions, dozens of major corporations have paid out a total of more than $15 billion in settlements around the country.

These are all group actions in which multiple plaintiffs sued the companies for widespread harm. Initially, major environmental lawsuits were brought as class actions. In the 1990s the U.S. Supreme Court put significant restrictions on such lawsuits, but trial lawyers have been able to achieve substantial settlements through the system of multi-district litigation in which cases from various jurisdictions are transferred to a single federal court with the aim of reaching a global settlement. MDLs are even more common in product liability cases (which Violation Tracker will tackle next).

Among the 104 environmental cases just added to the database, there are class actions and MDLs as well as suits brought by environmental organizations on behalf of communities.

Topping the list of settlement amounts are the cases brought in connection with the 2010 Deepwater Horizon catastrophe in the Gulf of Mexico. BP agreed to a $7 billion in 2012 settlement, which was separate from the more than $20 billion it later paid out to federal and state governments. Halliburton, also implicated in the disaster, paid a $1 billion private settlement. The other giant case was the $1.6 billion settlement Volkswagen reached with its dealerships affected by the automaker’s emissions cheating scandal. Like BP, VW also paid billions more in government settlements.

The company with the next highest total is Exxon Mobil, which has paid out more than $590 million in six different private environmental actions. Most of this amount came from a long-running lawsuit stemming from the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill off the coast of Alaska. The company was originally hit with a $5 billion punitive damages award, but it appealed all the way to the Supreme Court, which in 2008 slashed the amount to $507 million.

Four of Exxon’s other cases involved the gasoline additive MTBE. Communities and governments in various parts of the country have sued numerous oil companies to hold them responsible for MTBE contamination of water supplies from leaking underground oil tanks.

Another issue involving multiple companies is that of the PFOAs mentioned above in connection with DuPont. A variety of corporations have been sued for contaminating water supplies with these hazardous substances, also known as PFAs or forever chemicals because they do not break down in the body or the environment. DuPont and its spinoffs Chemours and Corteva have paid out hundreds of millions of dollars in these cases, while firms such as 3M and Georgia-Pacific have paid smaller amounts. Other suits are pending.

The dozens of other environmental cases have involved a wide range of toxic substances such as PCBs, dioxin, arsenic, TCE and vinyl chloride. The average of the 104 settlements is $150 million. Sixteen corporations have settlement totals above $100 million.

Missing from the list are major cases involving the role of corporations in exacerbating the climate crisis. Various suits have been brought, often by state and local governments and framed as shareholder actions, but so far none have resulted in significant monetary settlements. That is likely to change as the crisis grows worse and corporations are held culpable. When that happens, Violation Tracker will document the results.

Note: I would like to thank Suzanne Katzenstein and a group of her students at the Duke University Sanford School of Public Policy, who helped identify some of the environmental lawsuits discussed above.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/48126619532_f99720960b_k-4440c9ca18eb40d39353e807e7cd56ba.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.