Donald Trump likes to give the impression that he has made great strides in dismantling regulation. While there is no doubt that his administration and Republican allies in Congress are targeting many important safeguards for consumers and workers, the good news is that those protections in many respects are still alive and well.

Donald Trump likes to give the impression that he has made great strides in dismantling regulation. While there is no doubt that his administration and Republican allies in Congress are targeting many important safeguards for consumers and workers, the good news is that those protections in many respects are still alive and well.

This conclusion emerges from the data I have been collecting for an update of Violation Tracker that will be posted later this month. As a preview of that update, here are some examples of federal agencies that are still vigorously pursuing their mission of protecting the public.

Federal Trade Commission. In June the FTC, with the help of the Justice Department, prevailed in litigation against Dish Network over millions of illegal sales calls made to consumers in violation of Do Not Call regulations. The satellite TV provider was hit with $280 million in penalties.

Drug Enforcement Administration. The DEA is a regulatory entity as well as a law enforcement agency. In July it announced that Mallinckrodt, one of the largest manufacturers of generic oxycodone, had agreed to pay $35 million to settle allegations that it violated the Controlled Substances Act by failing to detect and report suspicious bulk orders of the drug.

Federal Reserve. The Fed continues to take action against both domestic and foreign banks that fail to exercise adequate controls over their foreign exchange trading, in the wake of a series of scandals about manipulation of that market. The Fed imposed a fine of $136 million on Germany’s Deutsche Bank and $246 million on France’s BNP Paribas.

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Last month the beleaguered CFPB ordered American Express to pay $95 million in redress to cardholders in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands for discriminatory practices against certain consumers with Spanish-language preferences.

Securities and Exchange Commission. In May the SEC announced that Barclays Capital would pay $97 million in reimbursements to customers who had been overcharged on mutual fund fees.

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. The EEOC announced that the Texas Roadhouse restaurant chain would pay $12 million to settle allegations that it discriminated against older employees by denying them front-of-the-house positions such as hosts, servers and bartenders.

Justice Department Antitrust Division. The DOJ announced that Nichicon Corporation would pay $42 million to resolve criminal price-fixing charges involving electrolytic capacitors.

Federal agencies are also finishing up cases dating back to the financial meltdown. For example, in July the Federal Housing Finance Agency said that it had reached a settlement under which the Royal Bank of Scotland will pay $5.5 billion to settle litigation relating to the sale of toxic securities to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. And the National Credit Union Administration said that UBS would pay $445 million to resolve a similar case.

It remains to be seen whether federal watchdogs can continue to pursue these kinds of cases, but for now they are not letting talk of deregulation prevent them from doing their job.

Note: The new version of Violation Tracker will also include an additional ten years of coverage back to 2000.

Since the beginning of 2010 the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission has resolved more than 200 cases of workplace discrimination based on race, religion or national origin and imposed penalties of more than $116 million on the employers involved.

Since the beginning of 2010 the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission has resolved more than 200 cases of workplace discrimination based on race, religion or national origin and imposed penalties of more than $116 million on the employers involved. The two biggest corporate crime stories of 2016 were cases not just of technical lawbreaking but also remarkable chutzpah. It was bad enough, as first came to light in 2015, that Volkswagen for years installed “cheat devices” in many of its cars to give deceptively low readings on emissions testing.

The two biggest corporate crime stories of 2016 were cases not just of technical lawbreaking but also remarkable chutzpah. It was bad enough, as first came to light in 2015, that Volkswagen for years installed “cheat devices” in many of its cars to give deceptively low readings on emissions testing. The chief executive of Wells Fargo would have us believe that more than 5,000 of his employees spontaneously became corrupt and decided to create bogus accounts for customers who were then charged fees for services they had not requested.

The chief executive of Wells Fargo would have us believe that more than 5,000 of his employees spontaneously became corrupt and decided to create bogus accounts for customers who were then charged fees for services they had not requested. Recent events have brought increasing attention to the persistence of racism in American life. While policing and criminal justice are currently in the spotlight, there are many more institutions that continue to exhibit systemic bias and must be held accountable.

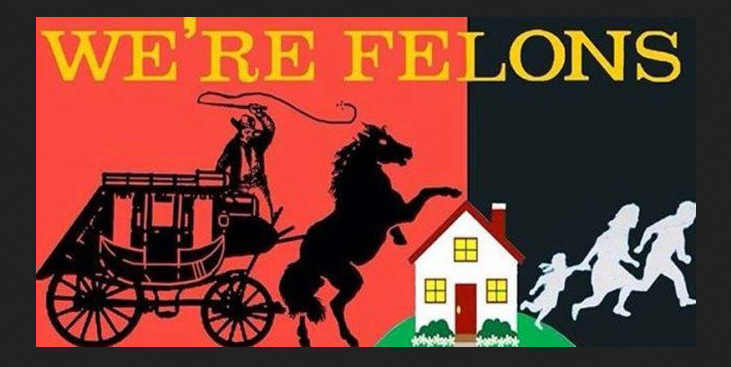

Recent events have brought increasing attention to the persistence of racism in American life. While policing and criminal justice are currently in the spotlight, there are many more institutions that continue to exhibit systemic bias and must be held accountable. For more than 30 years, Donald Trump has been almost continuously in the public eye, portraying himself as the epitome of business success and shrewd dealmaking.

For more than 30 years, Donald Trump has been almost continuously in the public eye, portraying himself as the epitome of business success and shrewd dealmaking. Restaurant giant Darden, which is being pressured by hedge funds to sell off both its Red Lobster and Olive Garden chains, got some good news recently when it

Restaurant giant Darden, which is being pressured by hedge funds to sell off both its Red Lobster and Olive Garden chains, got some good news recently when it

You must be logged in to post a comment.