By the standards of corporate law enforcement, the Justice Department is throwing the book at Insys Therapeutics. To resolve a civil and criminal case alleging that the company paid illegal kickbacks to healthcare providers to market its powerful opioid Subsys, DOJ required Insys to pay a total of $225 million in fines and forfeitures. Its operating subsidiary had to plead guilty to five counts of mail fraud.

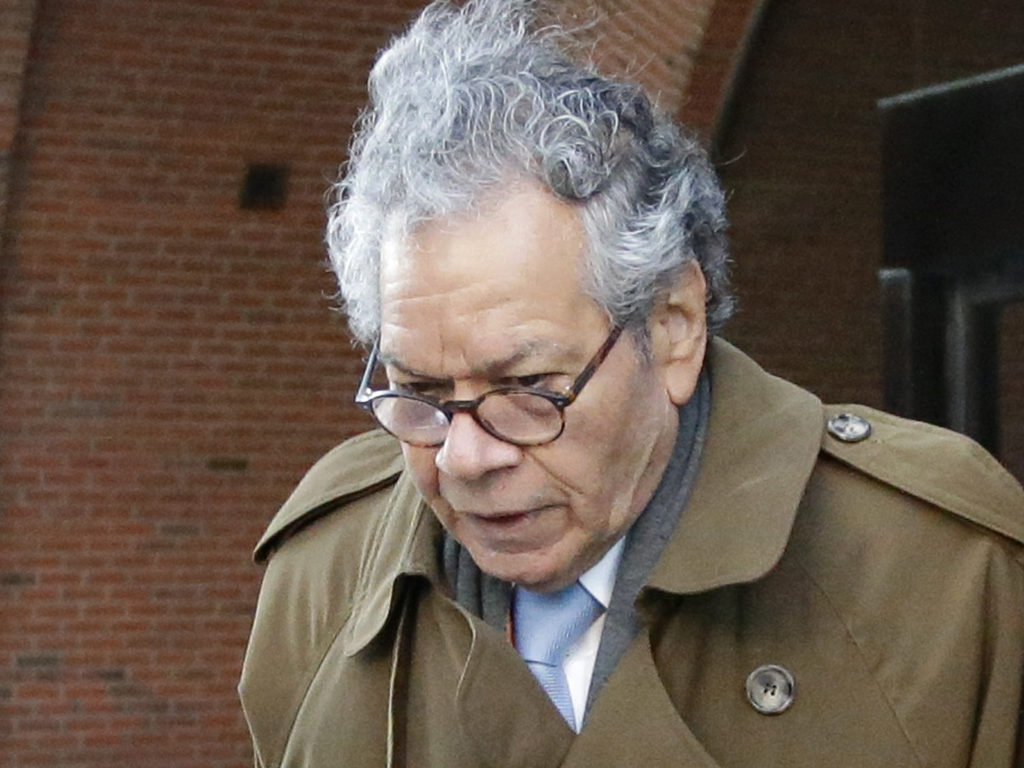

A few weeks earlier, a federal jury in Massachusetts delivered guilty verdicts against the Insys founder John Kapoor (photo) and four former top executives on racketeering charges relating to the kickbacks and other actions such as misleading insurance companies about the need for Subsys, which was supposed to be used in limited circumstances by cancer patients but which Insys tried to get prescribed more widely.

Although Insys itself was offered a deferred prosecution agreement, the company has felt the effects of these legal setbacks. It has been forced to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, its stock price has plunged, and it has agreed to sell off Subsys.

If Insys ends up going out of business entirely – and if Kapoor and the others end up in prison for a substantial period of time – this will serve as a warning to other players in the pharmaceutical industry that there can be dire consequences for serious misconduct.

Yet the challenge for prosecutors is whether they can apply similar punishments to larger malefactors in the drug business and related sectors. Insys, after all, had only $82 million in revenue last year and has a workforce of only 226. Its disappearance from the scene would not cause major disruptions.

Consider the case of Johnson & Johnson, with over $80 billion in annual revenues and about 135,000 employees. Despite a carefully cultivated image of purity in connection with its products for infants, J&J has been involved in a series of scandals over the past decade. Violation Tracker shows that it has paid out more than $3 billion in penalties.

The company has received a lot of unfavorable attention in recent months in connection with allegations that it covered up internal concerns about possible asbestos contamination of its baby powder and other talc-based products. J&J has been hit with a flood of lawsuits and has already received some massive adverse verdicts.

The company is also on the defensive for its role in the opioid crisis, facing a lawsuit brought by the state of Oklahoma, which has already collected substantial settlements in related cases brought against Purdue Pharma and Teva Pharmaceutics. J&J may wish it had settled.

An expert witness in the case recently accused the company of contributing to a “public health catastrophe” and charged that its behavior in some ways was even worse than that of widely vilified Purdue. It remains to be seen whether a company of the size and prominence of J&J will be subjected to the same kind of federal prosecutorial offensive launched against Insys. It is only when business giants face existential threats for their misdeeds that we may see real change in corporate behavior.