It may turn out that Donald Trump’s greatest contribution to American business is allowing the chief executives of tainted corporations to take a morally superior posture toward a presidency that seems to be completely devoid of principle. Their brands are boosted as his becomes increasingly toxic.

It is a good thing that big business is taking steps to separate itself from Trump. The collapse of the two advisory councils is not only a rebuke to Trump’s offensive comments on the events in Charlottesville but also an overdue retreat from entities that were set up mainly to foster the illusion that this administration is taking serious steps to reform the economy.

Yet it is dismaying that the moral vacuum created by Trump is being filled by the likes of Walmart chief executive Douglas McMillon, who got himself featured on the front page of the New York Times for a statement criticizing Trump.

For years the giant retailer was a national symbol of discriminatory practices. In 2009 it had to pay $17.5 million to settle a lawsuit alleging that it discriminated against African-Americans in the recruitment and hiring of truck drivers. The company was also widely accusing of gender discrimination. In 2010 the company was required to pay $11.7 million to settle a case brought by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and it was facing potential damages in the billions from a class action suit brought on behalf of more than 1 million female employees until the Supreme Court came to its rescue and threw out the case for what amounted to technical reasons.

In addition to discrimination, Walmart has been at the center of countless controversies involved wage theft, union-busting, tax avoidance, bribery and much more.

After Merck CEO Kenneth Frazier led the way among business critics of Trump’s embrace of white nationalism, the president struck back with a tweet referring to “ripoff drug prices.” While Trump was just being vindictive, it’s true that Merck’s reputation is far from untarnished.

In 2011 the drugmaker agreed to pay a $321 million criminal fine and a $628 million civil settlement to resolve allegations that it illegally promoted and marketed the painkiller Vioxx. This came after Merck had to remove the drug from the market in the wake of reports that the company for years covered up evidence of serious safety issues surrounding its blockbuster product. This is just one of a long list of its cases involving illegal marketing, overbilling, false claims and anti-competitive practices.

Another of the CEOs who spoke out in response to Trump’s comments was JPMorgan Chase’s Jamie Dimon. Earlier this year, the bank had to pay $53 million to settle a case brought by the U.S. Attorney in Manhattan accusing it of engaging in discrimination on the basis of race and national origin in its mortgage business.

JPMorgan Chase was one of the parties that helped bring about the financial collapse of a decade ago, and in 2013 it agreed to a $13 billion settlement of federal and state allegations relating to the packaging and sale of toxic mortgage-backed securities.

In 2015 JPMorgan had to pay a $550 million criminal fine to resolve federal charges that it and other large banks conspired to manipulate foreign exchange markets. There are many more entries in the corporate rap sheet of this company, which since the beginning of 2010 has had to pay out more than $28 billion in fines and settlements.

It would be difficult to find any members of the disbanded advisory councils whose companies have not engaged in serious misconduct of one sort or another.

Such is the peril of looking for paradigms of virtue in the business world. Corporate executives should, along with many others, speak out against Trump’s reprehensible comments, but they cannot lay claim to moral leadership.

For months the news has been filled with reports of suspicious meetings between Trump associates and Russian officials. Another category of meetings also deserves closer scrutiny: the encounters between Trump himself and top executives of scores of major corporations since Election Day. What do these companies want from the new administration?

For months the news has been filled with reports of suspicious meetings between Trump associates and Russian officials. Another category of meetings also deserves closer scrutiny: the encounters between Trump himself and top executives of scores of major corporations since Election Day. What do these companies want from the new administration? Trump’s travel ban and his rightwing Supreme Court pick are troubling in themselves, but they are also serving to deflect attention away from the plot by the administration and its Republican allies to undermine the regulation of business.

Trump’s travel ban and his rightwing Supreme Court pick are troubling in themselves, but they are also serving to deflect attention away from the plot by the administration and its Republican allies to undermine the regulation of business. The two biggest corporate crime stories of 2016 were cases not just of technical lawbreaking but also remarkable chutzpah. It was bad enough, as first came to light in 2015, that Volkswagen for years installed “cheat devices” in many of its cars to give deceptively low readings on emissions testing.

The two biggest corporate crime stories of 2016 were cases not just of technical lawbreaking but also remarkable chutzpah. It was bad enough, as first came to light in 2015, that Volkswagen for years installed “cheat devices” in many of its cars to give deceptively low readings on emissions testing.

Most cases of corporate misconduct are forgotten soon after a fine or settlement is announced, but the Wells Fargo phony account scandal seems to have real staying power. The company had to pay $185 million in penalties. CEO John Stumpf was forced to resign and pay back $41 million in compensation after being lacerated in two Congressional hearings. The city of Chicago and the California Treasurer cut some business ties with the bank.

Most cases of corporate misconduct are forgotten soon after a fine or settlement is announced, but the Wells Fargo phony account scandal seems to have real staying power. The company had to pay $185 million in penalties. CEO John Stumpf was forced to resign and pay back $41 million in compensation after being lacerated in two Congressional hearings. The city of Chicago and the California Treasurer cut some business ties with the bank. The False Claims Act sounds like the name of a Donald Trump comedy routine, but it is actually a 150-year-old law that is widely used to prosecute companies and individuals that seek to defraud the federal government. It is also the focus of the latest expansion of

The False Claims Act sounds like the name of a Donald Trump comedy routine, but it is actually a 150-year-old law that is widely used to prosecute companies and individuals that seek to defraud the federal government. It is also the focus of the latest expansion of

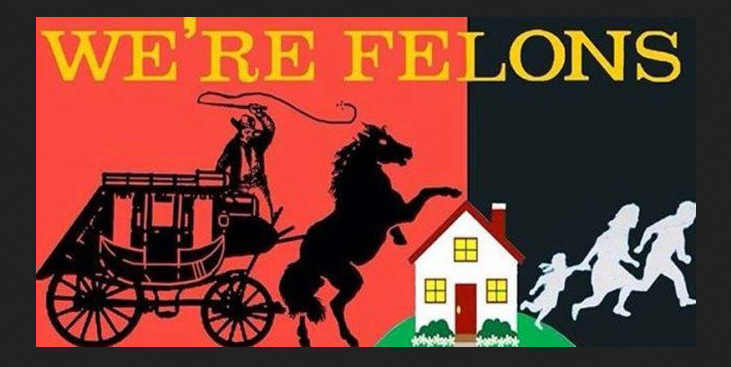

Donald Trump’s recent economic policy address portrayed an economy crippled by “overregulation.” This came on the heels of his convention acceptance speech depicting a country afflicted by a wave of street crime perpetrated by “illegal immigrants.”

Donald Trump’s recent economic policy address portrayed an economy crippled by “overregulation.” This came on the heels of his convention acceptance speech depicting a country afflicted by a wave of street crime perpetrated by “illegal immigrants.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.