Among the various roles played by Donald Trump during his State of the Union address was that of class warrior. He described a divide between “wealthy politicians and donors” living in gated communities while supposedly pushing for open borders and “working class Americans” who are “left to pay the price for illegal immigration—reduced jobs, lower wages, overburdened schools, hospitals that are so crowded you can’t get in, increased crime, and a depleted social safety net.”

Trump’s efforts to stir up worker resentment focus almost exclusively on situations in which foreigners can be depicted as the real culprits. He has no difficulty demonizing undocumented immigrants or the Chinese government, yet he rarely has any critical words for the traditional targets of populist anger: the super-wealthy and powerful corporations. On the contrary, those interests have enjoyed a privileged place during the Trump era, receiving lavish benefits in the form of tax breaks and regulatory rollbacks.

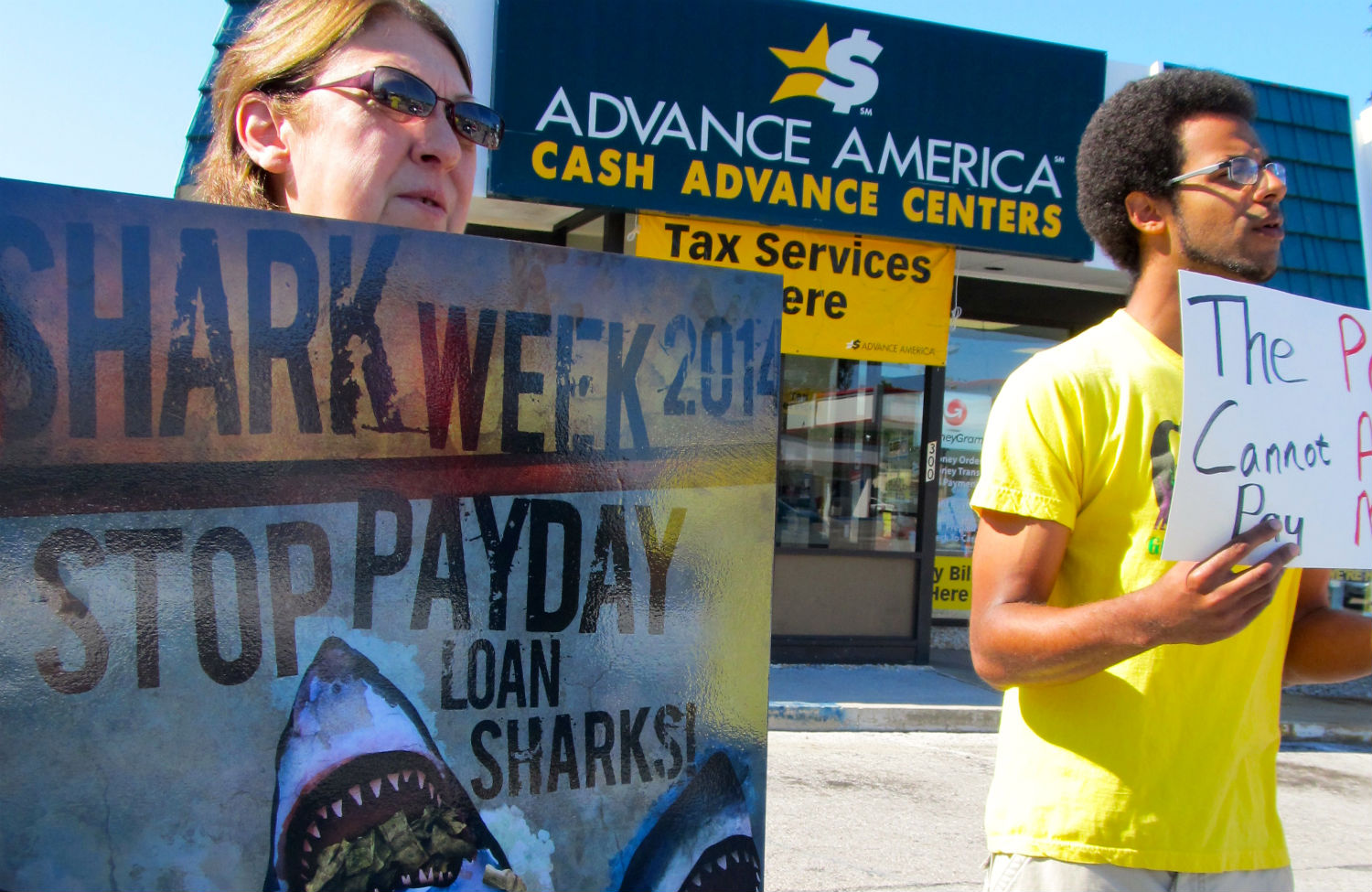

The latest example of the latter came less than 24 hours after Trump concluded his remarks in the House chamber. His Consumer Financial Protection Bureau announced plans to gut restrictions on payday lenders that were developed during the Obama Administration and were scheduled to take effect later this year.

The new rules were designed to put the responsibility on lenders to make sure their customers could afford the loans they were being offered. This was seen as a necessary safeguard in an industry notorious for charging astronomical interest rates to vulnerable customers who frequently ended up with massive debts after rolling over a series of short-term loans.

Prior to being neutered by the Trump Administration, the CFPB conducted a series of enforcement actions against payday lenders for egregious practices. For example, in 2014 the bureau brought a $10 million action against ACE Cash Express, alleging that the company “used illegal debt collection tactics – including harassment and false threats of lawsuits or criminal prosecution – to pressure overdue borrowers into taking out additional loans they could not afford.”

Payday lending has effectively been outlawed in about 20 states, but the Obama-era rules would have made a big difference in the rest of the country where the disreputable business is still allowed to function with annual interest rates of 300 percent or more. It will come as no surprise that many of the latter states are ones in which Trump enjoys high levels of popularity.

I can’t help but wonder what working class Trump supporters will think of this policy. Coal miners cannot be completely faulted for believing that Trump’s moves to dismantle power-plant emission controls may help them get work, but will struggling low-income families be cheered to learn that the administration is making it easier for payday lenders to exploit them rather than following the lead of the states that put a lid on usury?

Or, to put it more broadly, how long will Trump be able to pretend to be a working-class populist while pursuing the worst kind of plutocratic policies?