Republican members of Congress who abetted the plot to overturn the election will go down in infamy along with the disgraced 45th President himself. That applies both to the dead enders who still repeat the lies and those Senators and Representatives who abandoned the shameful crusade only after a mob whipped up by Trump invaded the Capitol.

There is another group of enablers who should be called to account: Corporate America. Sure, big business is now frantically trying to distance itself from Trump, with the National Association of Manufacturers going so far as to urge that Vice President Pence and the Cabinet invoke the 25th Amendment. Amid the chaos on Wednesday, the Business Roundtable called on Trump to put an end to the violence. In late November, a group of more than 160 chief executives urged the Trump Administration to accept Biden’s victory and cooperate in the transition process.

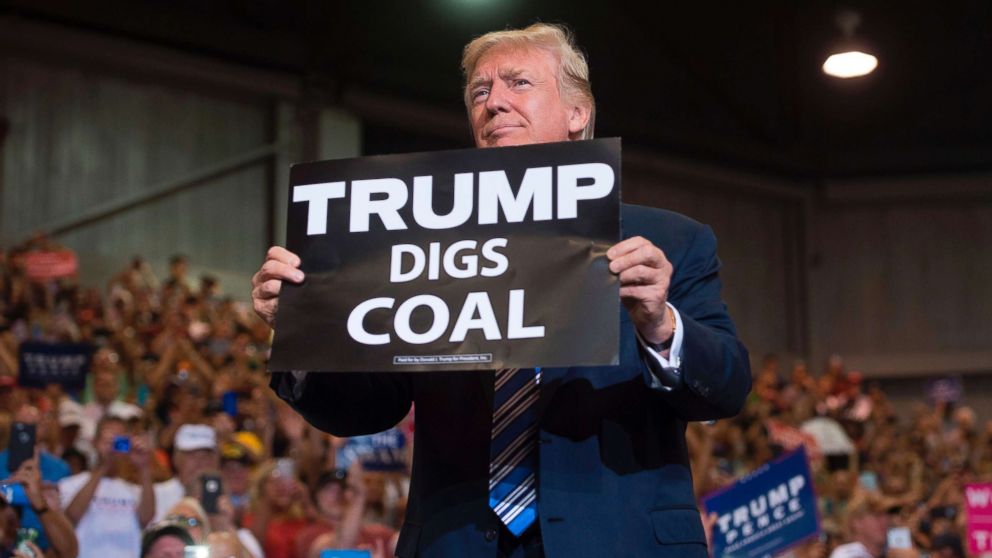

Yet, as with Congressional Republicans, these gestures came after four years of enabling Trump’s anti-democratic practices. While Trump moved steadily along the path to authoritarianism, large companies allowed themselves to be bought off with tax giveaways and regulatory rollbacks. There were occasional confrontations with corporations such as Carrier and General Motors over layoffs and offshoring, but these were bogus, reality-TV-type confrontations that amounted to nothing.

More significant were the policies adopted by a purportedly populist President that weakened labor unions, rolled back OSHA enforcement, curtailed fair labor standards and installed employer-friendly Secretaries of Labor.

Corporate America has also benefited from Trump’s retrograde environmental policies, especially the efforts to roll back limits on greenhouse gas emissions. On their way out the door, officials such as Andrew Wheeler of the EPA are trying to limit the options the Biden Administration will have to restore pollution controls.

Specific corporations have also been the beneficiaries of Trump’s policies. Military contractors such as Lockheed Martin have profited from the Administration’s use of arms sales to countries such as Saudi Arabia as a key element of its foreign policy. Telecommunications equipment companies such as Cisco benefitted from Trump’s campaign against its Chinese competitor Huawei.

Even companies chosen by Trump for his faux confrontations have profited from him or have assisted his accumulation of power. News corporations such as CNN gave Trump’s early rallies undue coverage and helped propel his political rise. Social media corporations for the most part have allowed Trump to disseminate hate speech and dangerous falsehoods.

Some prominent corporate figures have directly supported Trump, both with endorsements and substantial campaign contributions. These include Stephen Schwarzman of The Blackstone Group, Kelcy Warren of the pipeline company Energy Transfer Partners, and casino magnate Sheldon Adelson.

Other corporations and trade associations have sucked up to Trump and his family over the past four years. Last February, NAM, the organization now promoting the 25th Amendment, gave its Alexander Hamilton Award to Ivanka Trump.

On the whole, big business has offered little more than mild rebukes to Trump’s dangerous tendencies while reaping substantial benefits. Like Congressional Republicans, Corporate America needs to be held to account.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2016/09/09/DeathChamber-Texas.jpg)

.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.