Most cases of corporate misconduct are forgotten soon after a fine or settlement is announced, but the Wells Fargo phony account scandal seems to have real staying power. The company had to pay $185 million in penalties. CEO John Stumpf was forced to resign and pay back $41 million in compensation after being lacerated in two Congressional hearings. The city of Chicago and the California Treasurer cut some business ties with the bank.

Most cases of corporate misconduct are forgotten soon after a fine or settlement is announced, but the Wells Fargo phony account scandal seems to have real staying power. The company had to pay $185 million in penalties. CEO John Stumpf was forced to resign and pay back $41 million in compensation after being lacerated in two Congressional hearings. The city of Chicago and the California Treasurer cut some business ties with the bank.

Now Wells is facing a more serious legal challenge. It’s been reported that California Attorney General Kamala Harris is considering criminal identity theft charges against the bank over the millions of bogus accounts and the related fees that were improperly charged to customers. The AG’s office has demanded that Wells turn over a mountain of documents about accounts created not only in California but also in other states when California employees were involved.

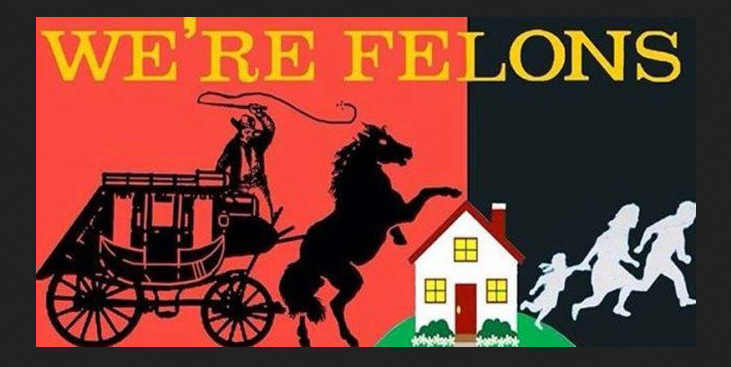

It’s too soon to say for sure, but this case and other potential criminal actions could have a catastrophic effort on Wells. Criminal cases against major banks are rare, and most of those are resolved through deferred prosecution or non-prosecution agreements that allow the corporation to avoid a conviction. An exception came last year when Citicorp, JPMorgan Chase and two foreign banks pleaded guilty to charges of manipulating the foreign exchange market. They had to get special waivers to continue operating in certain areas that normally exclude felons.

The Wells case may do more damage, given the scope of the misconduct and the fact that it involves the bank’s core business. In this way it is comparable to the scandal surrounding Volkswagen and its systematic fraud concerning emissions testing.

These two situations pose a challenging question: What should be done about a large corporation engaged in flagrant misconduct? Another monetary penalty is not going to make much difference. As Violation Tracker shows, even before the recent case Wells had paid out more than $10 billion in fines and settlements in some two dozen cases involving a variety of abuses.

Stumpf’s ouster was an important step, but is there any reason to think that the executives who remain are all that different? A boycott of the company’s services is merited, but it would have to be much bigger in scope to have a real impact.

The usual way that regulators and prosecutors handle criminal enterprises is to force them out of business, but these are usually relatively small operations. What should be done with an institution such as Wells, which has more than 260,000 employees, some 8,600 branches and offices, and 70 million (presumably real) customers?

The answer for dealing with Wells Fargo might be to break it up into a number of smaller companies that are kept under close supervision and barred from operating in riskier areas. In other words: use a variation of Glass-Steagall as a way of discouraging fraudulent behavior. Even better would be if these smaller institutions operated under employee ownership.

My point is that we need to get more creative in dealing with systemic corporate crime so we’re not forced to endure an endless series of scandals.

On those rare occasions when the current presidential race deals with policy rather than personalities, the focus tends to be on trade and immigration. Yet there is a potentially much greater threat to the well-being of U.S. workers that is receiving little attention: the technology revolution.

On those rare occasions when the current presidential race deals with policy rather than personalities, the focus tends to be on trade and immigration. Yet there is a potentially much greater threat to the well-being of U.S. workers that is receiving little attention: the technology revolution.

The False Claims Act sounds like the name of a Donald Trump comedy routine, but it is actually a 150-year-old law that is widely used to prosecute companies and individuals that seek to defraud the federal government. It is also the focus of the latest expansion of

The False Claims Act sounds like the name of a Donald Trump comedy routine, but it is actually a 150-year-old law that is widely used to prosecute companies and individuals that seek to defraud the federal government. It is also the focus of the latest expansion of

Apple’s

Apple’s  Price gouging by the producer of EpiPens has been creating a hardship for those suffering from severe allergies, but it is also revealing the truth about the one segment of the drug industry that was thought to have some decency.

Price gouging by the producer of EpiPens has been creating a hardship for those suffering from severe allergies, but it is also revealing the truth about the one segment of the drug industry that was thought to have some decency. The decision by the Justice Department to end its use of privately operated prison facilities is a long overdue reform and one that should also be adopted by the states. Yet the for-profit prison scandals are not limited to those involving companies such as Corrections Corporation of America that are in the business of managing entire correctional facilities.

The decision by the Justice Department to end its use of privately operated prison facilities is a long overdue reform and one that should also be adopted by the states. Yet the for-profit prison scandals are not limited to those involving companies such as Corrections Corporation of America that are in the business of managing entire correctional facilities.

You must be logged in to post a comment.